Understanding what properly developed Montessori curriculum should look like.

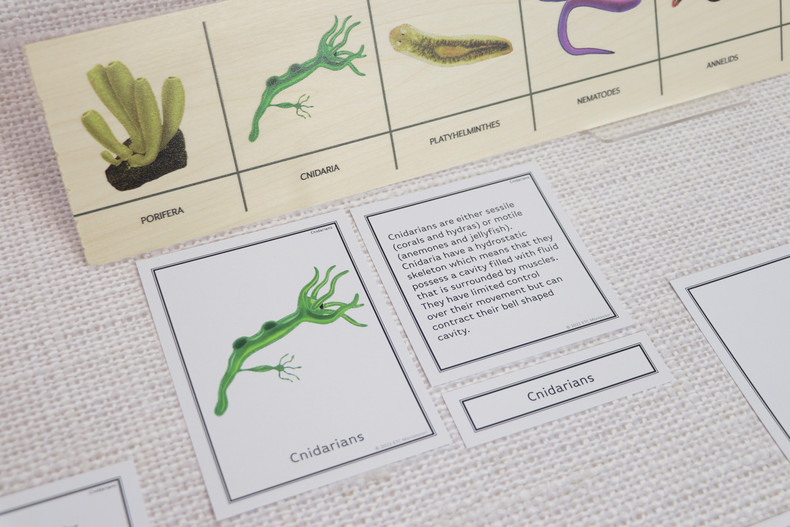

I can’t tell you how many classrooms I have been in where all I see is shelves full of three-part-cards, “what am I?” cards, and teachers who refer to them as “Montessori curriculum”. I also can’t tell you how many sites I have visited where someone with little or no Montessori training has decided to sell three-part nomenclature cards and call them Montessori curriculum. By definition, a curriculum is “the totality of student experiences that occur in the educational process”. Therefore, if three-part cards are nothing more than an abstract representation of something concrete, and their only role as a learning device is to build vocabulary or develop word recognition, then we should simply view them as a part of a broader curriculum, and NOT the curriculum.

Based on Dr. Montessori’s view, there are four planes of development. The first covers the ages of 0-6 years and it is often defined as the pursuit of physical independence. The second covers the ages of 6-12 years and is characterized as a stage of intellectual independence. The third covers the ages of 12-18 years and is characterized as the social stage. The fourth plane of development covers the ages of 18-24 and even through Dr. Montessori identified it; she did not elaborate on its characteristics. However, we can safely say and agree that individuals in this plane are characterized by the seeking of financial independence.

Our emphasis, in this article, will be on the second and third planes, because this is where we need to place a significant amount of energy. As a pedagogy, during the past twenty years, Montessori has grown exponentially. All indications point to this continued expansion and growth. The concept of Montessori has, and is becoming, more accepted into mainstream education. Yet, we still have curriculum publishers who fail to implement consistency, theme, or standards of any sort. Today, MACTE exists to set standards for training, while a different organization exists that houses the official blueprints for the designs of hardwood materials. Yet, we continue to fall short in the publishing world when it comes to Montessori curricula. It is time that we stopped looking at just the quality of the paper something is printed on and begin examining the finer points of what makes good curriculum, good. We need to applaud consistency, quality research, design calibration, intellectual innovation, and standards implementation.

With this in mind, we will look at two points that are essential to the development of suitable and true Montessori curricula.

1. Full Development of Thought

Isolation of difficulty in the true sense of the phrase is problematic in Montessori curriculum that is aimed at the second and third developmental planes. In seeking isolation of difficulty, for levels 6-12 and 12-18, a teacher needs to look at the full concepts that she is trying to present. Put simply, Montessori curriculum is cyclical, and interrelated, and therefore, the material being presented should reflect this. Once a concept has been identified, a series of activities and lessons are designed and used to support this concept. If we are to stay true to the Montessori pedagogical approach, then a true curriculum should provide a three-year cycle. A curriculum that is based on this three-year cycle takes full advantage of the full development of thought. Three-part cards alone are not designed or built to provide the content needed for a three-year cycle. Developmentally appropriate curriculum includes three-part cards, but it also includes the context in which these cards may be used.

If we are to stay true to the Montessori pedagogical approach, then a true curriculum should provide a three-year cycle.

So many Montessori publishers, fail or miss this concept of “Full Development of Thought”, and so there is a tradeoff between the method and the few extra dollars they can fetch by splitting things up - a separate purchase for nomenclature, a separate purchase for booklets, a separate purchase for wall charts. In its simplest form, nomenclature designed around the three-part card concept is based on a one-to-one association of picture and object, and therefore, cannot be considered curriculum; it's considered an activity. If publishers continue to tackle subjects by isolating them, the real losers will be the children since they will only see individual parts and lack the opportunity to make the connection of how these individual parts work as a whole.

2. Creating Relevance and Integration

The second part builds on “The Full Development of Thought” that we looked at above. In a curriculum, there should be opportunities for multiple extensions of the same activity. Simply put, a curriculum should provide repetition and additional exploration opportunities. Doing this allows for the integration of similar materials to be split between a variety of disciplinary concepts. By using a curriculum that has this built-in integrated approach, children can create connections between a concept in one area of study with a similar concept in a different area of study.

Creating developmentally appropriate, and well thought out integrated extensions, means that each child can learn within the context of various areas. An example of this structure may be found in the Ecology curriculum. Yes, a child can explore life cycles in the context of the environment through a couple of charts that identify its parts with labels. However, in a well-designed and properly developed curriculum, the same child will be able to go beyond labeling various parts. They can explore complex concepts such as what adaptations have been used allowing an organism to survive and go through a life cycle. There could be a well thought out research activity that delves on the environmental and economic impact that an organism has in each socio-economic context. As educators, we can and should clearly see the difference in learning between the two methods. In the latter example, we see the child move along from presentation of basic knowledge to application of knowledge.

If we are going to call ourselves Montessori educators, we need to start holding Montessori curriculum publishers at a higher standard.

If we are going to call ourselves Montessori educators, we need to start holding Montessori curriculum publishers at a higher standard. Publishers should begin acting as professional publishers that meet the broader needs of a pedagogical movement. It’s time we move beyond the simple three-part and “Who Am I?” cards. Publishers need to stop looking at what they produce as isolated successes and start creating materials that contain concepts that can be applied to the broader spectrum of knowledge. Doesn’t Montessori, as a methodology, a movement, a way of living and learning, deserve better? Yes, three-part cards do have a place in the educational context of Montessori pedagogy. Yes, we still need them to build vocabulary, and to introduce base knowledge, but if we, as educators, rely only on those basic methods of knowledge delivery, then it’s our children that will miss out. As we continue to educate the children of tomorrow it is becoming more evident that we not only seek curriculum that meets standards, but also provides for the deeper understanding that comes through well designed, fully multi-disciplinary integrated material that encourage children to think, explore, make connections, and understand.

Aki Margaritis is the Executive Director of ETC Montessori and holds teaching credentials for middle school and high school with advanced degrees in the areas of biology, math, and chemistry. He also holds a Montessori Secondary I credential from AMS.