I’m sure you have experienced it before- a concentration so deep that an hour passing felt like a minute. As you are absorbed in whatever activity you are doing, whether it be studying, playing sports, or even teaching, you are essentially unaware of the passage of time as your internal commentary becomes silent. Perhaps surprisingly, it is during these times that you are operating at your peak; your best and most efficient work is often done when in this state of intense focus. This is a state that many people refer to as being “in the zone” or entering a “flow state”. Although people have been aware of such states of focused concentration for thousands of years, it has only entered the realm of scientific study within the last fifty years.

The psychologist responsible for this modern investigation of flow is Mihály Csíkszentmihályi, who began studying the phenomena in the 1970s after becoming fascinated by the level of total concentration that artists would exhibit when entrenched in their work. In the forty plus years since this revelation, he has outlined not only what flow is (or at least he has begun to propose what it might be) but also how flow states affect us and how we can experience them more often.

According to modern flow researchers, a flow state is characterized by

Although each of these experiences can occur independently, it is only when they occur all together that the mental state can be referred to as a true flow state.

Unfortunately, flow states are not something that can happen just anytime- specific circumstances must be set up before a person is able to enter a flow state. Basically, the task at hand must have

Here it is, ladies and gentlemen- the connection to the Montessori method.

You may have just noticed that these flow state requirements are met in many ways by the prepared environment of Montessori classrooms! In Montessori, we provide the students with “clear sets of goals and progress” in several ways. We provide them with a workplan in elementary and above so that they know exactly what they should be working on at any given time- they never have to sit and wait for a teacher to tell them what to do next. We also set up the shelves in such a way that children can see both where they have come from and where they are going, simply by looking at the placement of the works. The works are arranged such that the child can immediately see their place in the curriculum and experience their movement forward simply by their progression through the shelves.

Montessori materials and teachers provide the “clear and immediate feedback” that is also required for flow states. Many materials are self-correcting, allowing the students to modulate their own work without the need for teacher intervention. This allows the children to become fully absorbed in their work without worrying about how they are doing- the material itself will provide them with that information! In cases where the teacher is the control of error, feedback is still relatively clear and immediate. When possible, Montessori teachers will check the children’s work immediately, while the child is watching. This allows the teacher and child to have direct communication about the work- any misunderstandings can be cleared up and the child can have a chance to correct any mistakes without having to task-switch back and forth between different works, which wastes time, compromises flow states, and reduces work quality.

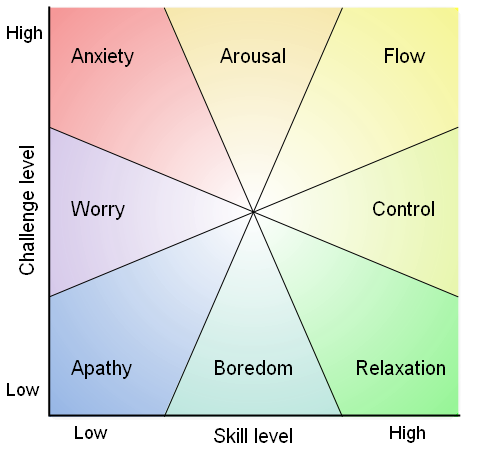

The final requirement, and perhaps the most difficult of all, is that there is a good match between perceived ability and the perceived difficulty of the task. Ideally, you want the child (or whoever is engaging in a task, even you!) to perceive the task as being only slightly above their current ability level. Tasks or activities that stretch an individual’s abilities, yet remain within reach, are most likely to produce flow states. If the task is too easy, the child may slip into boredom, thus losing motivation to continue the task. On the flip side, if the task is too difficult, the child will feel anxious and will avoid the task. If things align just right, however, the child will be able to enter a flow state. They will both be completely focused on the task at hand and feel rewarded by the experience. Yes, even if they are working hard while doing it!

The Montessori scope and sequence is set up to try to meet this requirement by default. The curriculum is designed so that the difficulty and complexity gradually increases as the child masters each concept. Because each child is able to work independently and at their own pace, it is much easier for the teacher to modulate the child’s environment to promote flow. If a child has mastered a math concept, the teacher is free to move him forward in the curriculum before he becomes bored of the task and loses motivation to work. Likewise, if a child is struggling with a difficult and abstract math concept, the teacher may bring out the bridging materials in order to bring the level of difficulty back to something that just barely stretches the child’s abilities. Because children are working independently, this can happen with each individual child, in each individual subject, without disrupting the studies of the rest of the class.

It’s a pretty amazing setup, and it seems to work the way you might expect. Studies have shown that children in Montessori middle school classrooms experienced flow significantly more often than students at a traditional middle school (Rathunde & Csikszentmihalyi, 2005)! Similar studies have not been conducted at the elementary ages (yet), but I suspect that the findings would be much the same.

This might all seem like a strange coincidence- after all, flow states were not studied by the scientific community until forty years ago, while Maria was developing her methodology over a hundred years ago! I would argue, however, that Maria Montessori was well aware of flow states and their importance- she just called them by a different name.

In The Absorbent Mind Montessori writes, “The child whose attention has once been held by a chosen object, while he concentrates his whole self on the repetition of the exercise, is a delivered soul in the sense of the spiritual safety of which we speak. From this moment, there is no need to worry about him - except to prepare an environment which satisfies his needs, and to remove obstacles which may bar his way to perfection" (Montessori, 1949). This focus on concentration occurs again and again in Montessori’s writings, and she is undoubtedly describing flow states. She speaks of how the child “concentrates his whole self on the repetition of the exercise”, an indicator that the child is motivated by, enjoying, and absorbed in the activity, exactly how Csíkszentmihályi defines flow states.

In The Advanced Montessori Method, Montessori writes about the child that “Not only is he spurred on to a work of intimate concentration immediately after his culminating effort, he preserves a permanent attitude of thought, of internal equilibrium of sustained interest in his environment.” This too fits with Csíkszentmihályi’s description of the extended effects flow states will have on a person’s psyche, even when they are not currently in flow! Mihály Csíkszentmihályi notes, “After an experience of flow, people experience their own self as being stronger and more vital than it was before. In a sense, the sense of self disappears during the experience, but afterwards comes back stronger than it was.” This description mirrors the observations made by Montessori in her classrooms, that children seemed altered, healthier, and more able to focus and listen after emerging from these intense states of concentration she describes.

It seems apparent that Maria Montessori knew exactly what she was doing when she set up classrooms to promote concentration and individual growth. She recognized that the concentration the children were experiencing was both psychologically healthy and extremely useful in both learning and self-development. It is only now, over sixty five years after her death, that people are beginning to fully recognize the greater significance of her insight into educational practice and mental development.

If you are interested in learning more about flow theory, I recommend reading Mihály Csíkszentmihályi’s works, especially Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. And, of course, I recommend reading Dr. Montessori’s original works to discover more about Montessori education and philosophy.

References

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). The psychology of optimal experience. Harper&Row, New York.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Flow and education. NAMTA journal, 22(2), 2-35.

Montessori, M. (1949). The absorbent mind. Adyar.

Montessori, M. (1917). The Advanced Montessori Method.. (Vol. 1). Frederick A. Stokes Company.

Maria, M. (1949). The Absorbent Mind.

Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2009). Flow theory and research. Handbook of positive psychology, 195-206.

Rathunde, K., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2005). Middle school students’ motivation and quality of experience: A comparison of Montessori and traditional school environments. American journal of education, 111(3), 341-371.

About the Author:

Lizby holds a degree in neuroscience, has Montessori Elementary I and II credentials, speaks French, some Spanish and Japanese. She enjoys scuba diving, photography, working with children and is enthusiastic about science and education.